1897 to 1921 is often referred to as the Heroic age of Antarctic Exploration.

Antarctica was just empty outline on the map

To fill in the map and discover Antarctica’s interior, humanities physical and mental limits would be tested to their breaking points with 100s of remarkable stories of survival and heroism.

Today we remember many of the famous names of that era:

Roald Amundsen, the first man to reach the South Pole.

Robert Falcon Scott, who died on his return journey from the Pole, forever thereafter known as Scott of the Antarctic.

Or the indomitable Ernest Shackleton whose famous failed attempt to cross the Antarctic on foot would end in one of the most heroic tales of survival the world has ever known.

For all the names we know today there are dozens of names forgotten to the pages of history.

We tend to remember the captains and the lords, the upper class gentlemen of the Royal Navy. Whilst forgetting the common man who suffered just as much, in many cases more, than their leaders.

But there is one name, who spent more time trudging across the ice than Scott of the Antarctic, more time mushing dogs than Shackleton, and stared death in the face with a smile too many times to count.

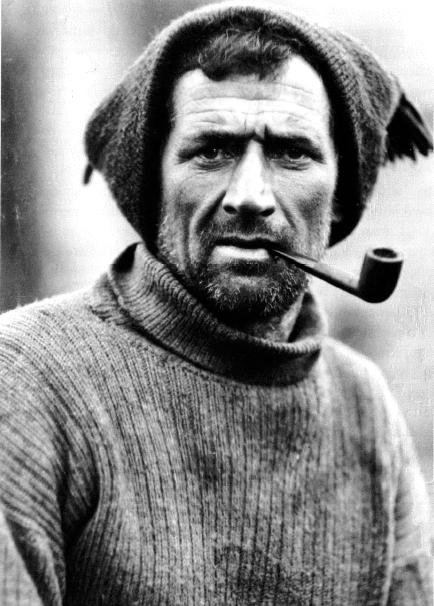

I speak, of course, of Tom Crean: The most badass Antarctic Explorer you’ve probably never heard of!

Unlike many of the famous Antarctic explorers, Crean didn’t come from a wealthy background, or grow up amongst the mountains and snow.

He was just an ordinary man, from a tiny little town called Anascual in Country Kerry in rural Ireland. He grew up on a farm to a poor family.

Eventually, like many before him, he escaped the monotony and poverty of rural Ireland by joining the Royal Navy in 1893 at the age of 15 or 16 (reports differ).

Nearly everything we know about Tom Crean and his exploits in the Antarctic comes from the accounts of his crewmates. For unlike many of them, Crean never kept a diary of his own.

Crean wasn’t initially assigned to any Antarctic mission, it was pure serendipity.

In 1901, the ship he was stationed on, the Ringarooma, was in New Zealand just as Scott’s Discovery Expedition was making final preparations for their mission to the Antarctic, where Scott would make his attempt at reaching the South Pole.

The Ringarooma was ordered to assist the Discovery in their final preparations.

During this time, one of the Discovery crew deserted, leaving them one man down.

Tom Crean volunteered and just like that his life would change forever.

He had never been to the Antarctic, never travelled on snow before. It’s likely he had no idea what he was getting himself in for but it was something new, something adventurous and he wanted to be a part of that.

Discovery Expedition, 1901–1904

On December 21st, 1901 Crean set sail for the Antarctic with Scott and 46 other men.

It would be 3 years before they would return to civilization again.

On 8 February 1902, the Discovery arrived in McMurdo Sound.

The men established the base , unloading supplies and preparing all their scientific instruments and preparing for Scotts attempts on the South Pole.

This base would become “Hut Point”

Scott never fully appreciated the advantages of using sledging dogs on the snow.

As so, most of the gear and food depots used for the expedition were put in place by teams of man-haulers.

Literally men in harnesses pulling for all their worth.

Crean proved to be one of the best man-haulers amongst the crew. He logged a total of 149 days in the harness throughout the expedition. Only 7 more men of the 48 logged more time.

The conditions were brutal but one of Creans most important qualities shone through the freezing temperatures; he had a great sense of humour, ever the optimist with a smile on his face.

Albert Armitage, the second in command, later wrote that “Crean was an Irishman with a fund of wit and an even temper which nothing disturbed.”

Cream also seemed to be impervious to the cold. On a trip across the ice with Bowers, Hooper and Nelson, the 4 men were crammed into a small tent for the night as the temperatures plummeted to -38 degrees Fahrenheit / -39 degrees celsius.

Cream somehow slipped head first out of the tent. This let the cold air in which woke the other men but Cream himself had slept through the whole experience undisturbed.

Much of the Discovery expedition Crean spent on sledging trips across the Ross Ice Shelf, setting up depots for Scotts’, Shackletons and Wilson’s attempt on the South Pole.

In the Winter of 1902 the Discovery became trapped in the ice,it was assumed the ice would break up early in 1903.

On November 2nd 1902, Scott, Shackleton and Wilson set off on their attempt to reach the south pole.

But It was a failed endeavour, their lack of experience with the dogs and their diet seriously hampered them as scurvy set it. Shackleton especially was in a bad way.

They reached their Furthest South at 82°17′S but had to turn back.

Their return journey was a very close call but eventually they returned to the ship on February 3rd 1903.

The ship was still ice-locked but a relief ship called Morning arrived bringing vital supplies and also brought some of the ailing crew home, including Shackleton.

Tom Crean stayed as the expedition explored other areas of the Antarctic.

Efforts to free the Discovery from the ice during the summer of 1902 and 03 both failed and just as Scott was beginning to think he would need to abandon ship in February 1904 the ice suddenly broke up and the discovery was on her way back to New Zealand and civilisation.

Whilst many tremendous firsts were achieved on the Discovery Expedition, it was generally viewed as a failed mission, even if Scott achieved heroic status on his return.

For Crean, it provided invaluable experiences on the ice and snow and most importantly of all, it gave him the opportunity to showcase to both Scott and Shackleton that he was a capable and reliable team member for any future expeditions.

On returning to regular naval duty, Scott recommended that Crean be promoted to petty officer.

Between expeditions, 1904–1910

After the Discovery expedition Scott made sure that Crean served with him on whichever ship he was on.

In 1906 Crean served with Scott on the Victorious, then the Albemarle, the Essex and the Bulwark.

Scott was already planning his next expedition and knew Crean would be joining him.

During this time Shackleton had his own expedition on the Nimrod. Despite reaching a new furthest south of 88°23’S, Shackleton again failed to reach the South Pole.

Upon hearing of Shackleton’s failed attempt, Scott remarked to Crean: “I think we’d better have a shot next.”

Terra Nova Expedition, 1910–1913

In june 1910 the Terra Nova set sail with Crean aboard. He was one of the first men Scott recruited and crucially one of the very few crew members who had Antarctic experience.

They arrived back in Hut Point in January 1911.

Scott would again attempt to reach the South Pole.

In preparing for this attempt, Tom Crean was involved in setting up the ‘One Ton Depot’ which was 130 miles/210km from Hut Point.

On the return journey with Apsley Cherry-Garrard and Henry Bowers, the 3 men were camping when during the night the ice broke up around them.

The men were adrift on a sea of ice floes and separated from their sledges.

Crean, took a bold decision and performed a daring and heroic act. He began leaping from flow to flow until he got to the Barrier’s edge, a sheer ice cliff.

He somehow managed to climb up the barrier edge and was able to return to Hut Point to get help.

The rescue party was able to recover both Cherry-Garrard and Bowers. Crean’s actions undoubtedly saved the men’s lives that day.

Scott found the experience of men like Crean invaluable, writing:

I am greatly struck with the advantages of experience in crean and lashly for all work about the camps

In November 1911, Scott set off on his second attempt at the South Pole. He was accompanied by 15 men, including Crean. There were 4 teams of 4 men.

Only one team would attempt the final leg of the journey to the South Pole.

At regular intervals the supporting parties would return to Hut Point.

Crean was in the final group of eight men that marched on to the polar plateau and reached 87°32’S, 168 statute miles (270 km) from the pole.

On 4 January 1912, Scott selected his final polar party:

Crean, William Lashly and Edward Evans were ordered to return to base.

While Scott, Edgar Evans, Edward Wilson, Bowers and Lawrence Oates continued to the pole.

Scott made a fatal flaw in picking 5 men instead of 4.

The entire expedition was built around teams of 4 men. It would take longer to boil water for food, conditions would be more cramped.

And Crucially Edgar Evans was suffering a hand injury which he concealed from Scott.

The expedition surgeon Edward L Atkinson, who accompanied the southern group earlier on had recommended both Crean and Lashly be in the final 4.

Many suggest that had either Crean or Lashly been in the group they could very well have completed the journey.

But sadly, it was a fatal mistake by Scott.

All 5 men would perish in the cold. They would reach the South Pole, but not have enough energy to reach the next supply depot.

They died a mere 11 miles away from the One Ton Depot.

Scott famous last entry in his diary:

Every day we have been ready to start for our depot 11 miles away, but outside the door of the tent it remains a scene of whirling drift. I do not think we can hope for any better things now. We shall stick it out to the end, but we are getting weaker, of course, and the end cannot be far. It seems a pity but I do not think I can write more. R. Scott. Last entry. For God’s sake look after our people.

As Crean, Lashly and Evans stood watching and waving as the 5 men set off towards the South Pole, they would be the last men to see them alive.

Scott’s decision to take 5 men instead of 4 also severely endangered the return journey of the 3 man team.

The return journey of 700 statue miles (1100km) was a difficult one. The 3 men got lost on the Beardmore Glacier and had to take a long detour around a large icefall.

Running low on supplies, they took a desperate gamble and the group decided they would climb on to their sledge and slide down the icefall with no way of controlling it or knowing what they would face.

It was the act of desperate men who slide down 2000 feet (600 meters) over creavass ridden icefalls before eventually tumbling to a stop over an ice ridge.

Evans later wrote: “How we ever escaped entirely uninjured is beyond me to explain”.

The desperate gamble won out and they reached their supply depot two days later.

However, their trip wasn’t over yet, they still had to navigate down the glacier.

Lashly wrote: “I cannot describe the maze we got into and the hairbreadth escapes we have had to pass through.”

Once passed the glacier and on the smoother barrier surface, Evans, the navigator, was suffering badly from snow blindness and the early stages of scurvy.

By early February he was in great pain, his joints were swollen and discoloured, and he was passing blood.

Through the efforts of Crean and Lashly the group struggled towards One Ton Depot, which they reached on 11 February.

It was here that Evans collapsed. Crean having thought he had died began to cry and according to Evan’s ‘his hot tears fell on my face” but Evans was still alive but on the verge of death.

Lashly and Crean began to pull Evans on the sledge the final 100 mile stretch to Hut Point.

On 18 February they arrived at Corner Camp, still 35 statute miles (56 km) from Hut Point.

With only one or two days’ food rations left and still four or five days’ man-hauling to do.

It was decided that Crean should go on alone, to fetch help.

After already battling Antarctica for 1600 miles, with only one peice chocolate and three sledding biscuits, no tent or survival equipment Crean made the solo march to Hut Point in 18 hours.

Crean arrived into Hut Point to alert his crewmates of the dire situation Lashly and Evans were in.

Two hours after Crean arrived at Hut Point a deadly blizzard rolled in. If Crean was caught out in that blizzard he would surely have perished.

Both Lashly and Evans were brought to base camp alive after the blizzard passed.

Once again the individual actions of Crean would help save his fellow explorers.

In a rare letter from Crean he later modestly wrote of the incredible march:

“So it fell to my lot to do the 30 miles for help, and only a couple of biscuits and a stick of chocolate to do it. Well, sir, I was very weak when I reached the hut.”

The rest of the expedition was a sombre affair,as the party eventually realized that Scott and the others had inevitably died on their attempt.

Crean’s jovial and playful nature for sure helped the men through that dark Winter. As Frank Debenham wrote that “in the winter it was once again Crean who was the mainstay for cheerfulness in the now depleted mess deck part of the hut.”

When travel was again possible Crean and 10 others were part of a search party that found the remains of the polar party.

On 12th November Crean spotted a strange cairn of snow on the horizon.

This was Scott’s tent with snow piled up against it.

It contained the bodies of Scott, Wilson, and Bowers. The bodies of Oates and Evans were never found but Scott’s diary reports they had died earlier.

Crean later wrote, referring to Scott in understated fashion, that he had “lost a good friend”.

On 12 February 1913 Crean and the remaining crew of the Terra Nova arrived in Lyttelton, New Zealand, and shortly after returned to England.

The surviving members of the expedition were awarded Polar Medals by King George.

And Crean and Lashly were both awarded the Albert Medal, 2nd Class for saving Evans’s life.

Crean was also promoted to the rank of chief petty officer.

Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition (Endurance Expedition), 1914–1917

Whilst Scott had died on his expedition, the Norwegian Roald Amundsen was successful in his, becoming the first man to reach the South Pole.

The last great prize of exploration had been claimed.

Shackleton though, not to be outdone began to plan an ambitious expedition to cross Antarctica on foot passing through the South Pole.

This would become the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition but it’s more commonly known as the Endurance Expedition, named after the expedition ship.

Shackleton knew Crean well from the Discovery Expedition, and also knew of his heroics on Scott’s last expedition and recruited Crean as a second officer for the Endurance Expedition.

On October 26th 1914 The Endurance left Buenos Aires with a crew of 28 men, including the unluckiest stowaway in human history Perce Blackborow.

They arrived at the remote whaling station Grytviken in the South Georgia Island, where they took on one tonne of whale blubber to sustain them.

Whilst there the seasoned whalers told Shackleton they had never seen the Weddell Sea so bad. Horrendous weather and ice packs.

Shackleton was determined though and pushed on through the ice packs. Progress was painfully slow and Shackleton wrote:

I had been prepared for evil conditions in the Weddell Sea, but had hoped that the pack would be loose. What we were encountering was fairly dense pack of a very obstinate character.

By mid-January though the ship had made its way within landing distance of Antarctica, rather than land though Shackleton wanted to push further south, so there would be less distance to trek onland.

This decision was a costly one though.

On 19 January 1915 the Endurance became trapped in the Weddell Sea pack ice.

The crew tried to free her from the ice but to no avail.

During this attempt Crean narrowly escaped being crushed between the boat and ice when the ice suddenly moved.

Trapped in the ice the Endurance and her crew were at the mercy of the currents and it soon became apparent that the ship would be trapped for the winter.

The men maintained their routine on the ship throughout the months of darkness.

The current was pushing them further north, with the hope that the ice would break and free the endurance and she would find land once again.

However, the pressure from the ice floes was immense on Endurances Hull.

Worsley described the pressure as like being “thrown to and fro like a shuttlecock a dozen times”

On 27 October 1915 Shackleton ordered the men to abandon ship as the pressure from the ice could snap the Endurance at any moment.

The crew now came face to face with the prospect of establishing a base on the precarious floating island of ice.

They took all the supplies and 3 lifeboats off the ship.

The ship drifted in the ice for months, eventually being crushed and sinking on 21st of November.

Shackletons initial plan was to drag all the food, gear and life boats across the ice pack to Robertson Island, some 200 statute miles (320km) away.

However, this proved an impossible feat. After a tense mutiny from the carpenter, McNish, the futility of Shackleton’s plan was abandoned.

All they could do was wait. Wait for the ice to drift further north and break up.

Shackleton named the camp ‘ Patience Camp’.

In the meantime they would have to live on the ice, which was only a few feet thick.

As the men slept at night they could hear the tumultuous sea below them.

It wasn’t until April 9th, 4 and half months after the Endurance had sunk that the ice began to break up

The nearest island was Elephant island. An uninhabited stark rock jutting out from the sea.

The men stocked up the 3 lifeboats. The largest the James Caird was captained by Shackleton. Then the Dudley Docker was captained by Worsely.

Crean was on the 3rd boat the Stancomb Wills which was originally captained by Hubert Hudson but it soon became apparent that he had suffered a mental breakdown and Crean took charge of the boat.

With temperature as low -20 Degrees Fahrenheit (-29 degree celsius) the men rowed 5 days, occasionally having to stop at small ice flows and camp for the night.

On the 4th night Elephant island was spotted in the distance but a severe storm rolled in and the men had to battle one more night for it to pass.

The next day, they eventually got to shore and felt firm ground beneath their feet for the first time in months.

Upon reaching Elephant Island, Crean was one of the “four fittest men” selected to find a safe camping-ground, as their original landing spot wasn’t suitable.

The men were on terra firma once again but they were far from saved.

Elephant island is one of the most isolated places in the world and no ship would ever happen upon the men no matter how long they managed to survive.

Shackleton decided that, rather than waiting for a rescue ship that would probably never arrive, one of the lifeboats should be strengthened so that a crew could sail it to South Georgia and arrange a rescue.

The Carpenter, and former mutineer, Harry McNish, set about to make the James Caird, the largest of the lifeboats, as sea worthy as possible.

Shackleton would take 5 men with him whilst the rest would hunker down on Elephant Island and wait for rescue.

The 5 men were:

Frank Worsley, an expert navigator.

Harry McNish, the carpenter. Many suspect Shackleton took him so he wouldn’t cause trouble on Elephant Island

Two young seaman John Vincent and Timothy McCarty and, of course, the ever reliable Tom Crean.

Frank Wild would be left in charge of the men on Elephant Island. Wild had wanted the dependable Crean to stay with the men, his good spirits would surely have helped them but Crean begged Shackleton to be included in James Caird crew.

The 800-nautical-mile (1,500 km) boat journey to South Georgia, described by polar historian Caroline Alexander as one of the most extraordinary feats of seamanship and navigation in recorded history, took 17 days through gales and snow squalls, in seas which the navigator, Frank Worsley, described as a “mountainous westerly swell”.

The men were in cramped conditions and faced extreme cold and little food.

THey had two barrels of drinking water but it was later discovered that one of them had been contaminated with salt water.

Shackleton, in his later account of the journey, recalled Crean’s tuneless singing at the tiller: “He always sang when he was steering, and nobody ever discovered what the song was … but somehow it was cheerful”.

After setting off on 24 April 1916 with just the barest navigational equipment, they reached South Georgia on 10 May 1916.

Frank Worsleys skills as a navigator deserve the highest of praise. For sure, without him, the men would never have made it to South Georgia.

The men made landfall on the uninhabited southern coast, having decided it was too risky to try to navigate around the island.

Shackleton decided that the 3 fittest men, himself, Worsley and Crean would trek across the unknown interior of the island to the whaling station in Strommness Bay.

On paper it was only a 30mile (48km) trek but the South Georgia interior had never been crossed before and never mapped.

The terrain was mountainous and covered in glaciers and crevasses.

The 3 men would carry no tent or sleeping bag or map.

Mcnish took some nails from the boat and hammered them in their shoes for crude crampons.

Apart from that all they carried was 50ft of rope, a carpenter’s adze, in lieu of an ice axe, a primus stove with enough fuel for 6 meals of hoosh, with a simple concoction of ice, sledging biscuits and Pemmican.

Pemmican was a staple of the Antarctic Explorers which is a nutritious mix of tallow, dried meat and berries.

The trek was a dangerous one, especially considering the physical condition of the men. Many times the men had to turn back, first at Fortuna bay as they realized they were walking back out to sea across a frozen plane and then numerous times as they tried to find a safe way to pass over the mountains.

Again and again they had to expend precious energy to climb up a mountain only to turn back after finding no safe way to continue.

On one of these peaks the men realized that they needed to descend rapidly or the freezing night temperatures would kill them.

They made the drastic decision, one Crean had made before, to slide down the mountain and throw caution to the wind.

The coiled their rope into a makeshift sledge and clung to each other as they slid down the mountain, unscathed.

Shackleton recalled once at the bottom, prompted by Crean, the 3 men shook each others hands.

Eventually they found a way through the mountains at 6.30am Shackleton thought he heard a far off whistle.

The whistle would be used to rouse the whalers to work.

The men waited for 7am and sure enough they each heard the whalers whistle. The first sound of civilisation the men had heard in over 2 years.

They still had to relay their way down one more mountain using the carpenters adze to chisel steps into the ice and then use the rope to descend an icy cold waterfall.

But eventually they arrived in the Stromness whaling station, looking like the walking dead.

Their hair was long and matted, their faces blackened from cooking with the blubber stoves.

Worsley remarked they were ‘the world’s dirtiest men’.

They quickly organized a boat to pick up the three men on the other side of South Georgia.

And it took Shackleton, Worsley and Crean a further three months and four attempts by ship to rescue the other 22 men still on Elephant Island.

When they finally got through, all men were safe and accounted for and Crean was on hand to toss out packs of cigarettes to his grateful crew mates.

After Exploring Antarctica

Returning to civilization Crean resumed his naval duties, eventually retiring in 1920.

Unlike many of the other men he never wrote a book or went on speaking tours about his remarkable adventures.

Instead in he return to his little home town on Annascaul, got married, started a family and open up a little pub called:

The South Pole Inn.

It’s still there to this day.

Tom Crean’s legacy is greatly admired by all those in the Antarctic Exploration community.

He even has a mountain in Antarctica named after him, Mount Crean. And the jagged glacier the 3 men cross in South Georgia is named after him too.

However, his name is not as widely known as the likes of Scott, or Shackleton or Amundsen and Crean himself would have probably been happy with that!

But without doubt his achievements and perseverance and eternal sense of optimism in face of seemingly inevitable death are something any future generation can be inspired by.